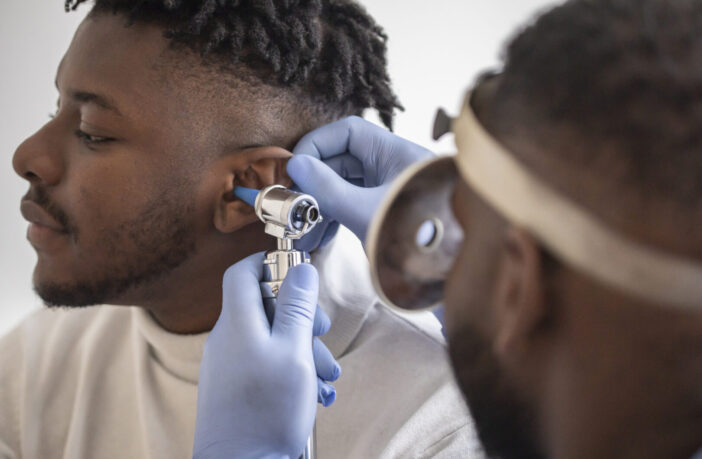

This week the House Judiciary Committee’s subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship held a hearing titled “Is There a Doctor in the House? The Role of Immigrant Physicians in the U.S. Healthcare System.” The hearing posed the following question: given America’s doctor shortage, should we do more to import foreign doctors to the United States?

The problem seems simple on paper. There aren’t enough doctors in the United States – and particularly in underserved and rural areas. Why wouldn’t we prioritize hiring foreign physicians to close that gap? The real situation is much more complicated.

Congress posed this question at various times over the years, including in April 2020 when two Republican senators penned a letter arguing for the importation of more foreign nurses to aid in the nation’s battle against COVID-19. At the time, FAIR pointed out that the reasons for the nursing shortage were complex, including that “U.S. nursing schools turned away 75,029 qualified applicants from baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs in 2018 with most schools pointing to faculty shortages as a reason for not accepting all qualified applicants.” A report from the Boston Federal Reserve Bank also found that importing foreign nurses was hardly the panacea some portrayed it as.

The doctor shortage is similar. Kevin Lynn, the founder of the medical advocacy group Doctors Without Jobs (DWJ) argued in testimony before the subcommittee that the real reason for the doctor shortage is a growing reality of qualified U.S. doctors not matching to residency programs. Lynn wrote in his opening statement that “thousands of American medical doctors – U.S. physicians – have been denied the right to practice medicine. This is one of the most unreported stories, and one of the most ignored situations by our elected officials and medical community leadership in America, including our medical schools and the various governing bodies who purport to represent physicians.”

There is a shortage of between 20,000 to 60,000 physicians in the U.S., according to Unmatched and Unemployed Doctors of America. DWJ also noted that in 2021 more than 7,400 medical school graduates who are U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents did not match to a residency. Without residency, these medical school graduates are not able to practice and cannot earn their medical license. DWJ argues that this mismatch is one of the key drivers to the current doctor shortage.

There is another angle to this problem as well. In the hearing, a number of representatives made note of the lack of doctors and physicians in rural or otherwise underserved communities. Again, on paper it may appear to make sense to place foreign physicians in these localities. But it just isn’t that simple, especially considering that foreign doctors admitted under immigrant visas could, and likely would, become citizens one day. Would they stay in the same locality, or venture out to larger metropolitan areas to earn more money and pursue other opportunities? This same tired line of thinking inspired the EB-5 investor visa. Supporters point to the program’s supposed promise to infuse foreign capital into investment projects in “targeted employment areas” that could revitalize struggling localities. This almost never happens, and many EB-5 investors prop up their businesses in already thriving areas.

This is to say that the root causes are deeper than there not being enough foreign doctors, and it would be naïve to imagine that foreign doctors would stay in these underserved communities after becoming a citizen and being free to move somewhere else for more opportunities.

The problem is complex, and a simple band aid solution of importing even more foreign physicians will do nothing to solve this problem. It will require a multifaceted approach involving improving the matching process for U.S. medical school graduates and prioritizing the development of medical career opportunities in underserved areas.

1 Comment

Pingback: Do We Really Need Foreign Doctors to Solve the Physician Shortage? – India Inc Blog